‘Death: A Graveside Companion’ offers an outlet for your morbid curiosity

Death: A Graveside Companion makes for an unusual coffee-table book, with its coppery etched Grim Reaper on the cover. Yet you may be surprised by how much fun it is to pore through the book’s lavish artwork of skulls, cadavers and fanciful imaginings of the afterlife.

There is, after all, a reason for the term “morbid curiosity.” It’s only natural for people to try to understand and come to terms with their inevitable demise, and as the book reveals, it is only in modern Western society that the topic of death has become so taboo. Even as recently as Victorian times, the book notes, the dead were laid out in the family parlor, their hair cut off and twisted to make decorative mementos to hang on the wall.

As a founder of New York City’s now-closed Morbid Anatomy Museum, Joanna Ebenstein has set out to help change modern attitudes, by giving us permission to let our morbid curiosity loose. “It is my hope that this book might act as a gesture towards redeeming death, to invite it back into our world in some small way,” she writes. “It is precisely by keeping death close at hand and coming to terms with its inevitability that we are able to lead full rich lives.”

She brings together 1,000 images of historical artwork, illustrations and artifacts showcasing humankind’s ongoing quest to imagine and find meaning in death, along with 19 essays by a diverse set of writers, art experts and scientific thinkers. The writings cover spiritual and symbolic aspects of death, such as the origins of Mexico’s Day of the Dead, and the surprising variety of death-themed amusements over the years. An early Coney Island attraction, for instance, re-created the experience of being buried alive. Some essays delve into scientific history, such as miniature crime scenes used in forensic science and the history of cadavers in the study of anatomy.

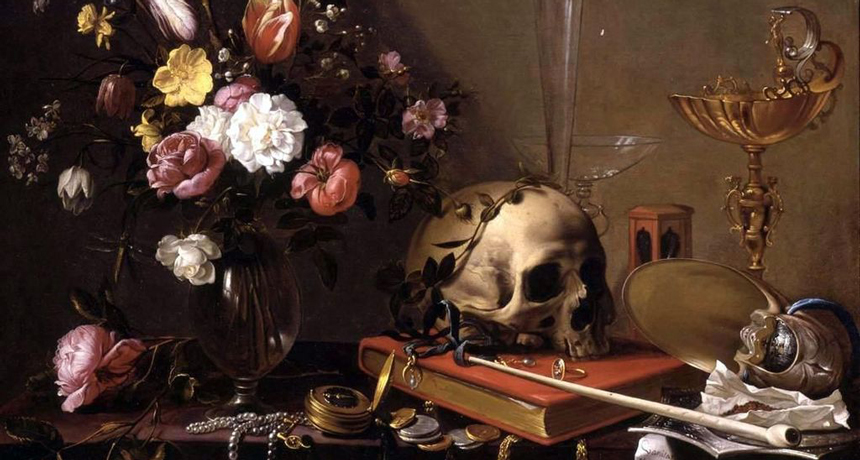

While the essays are illuminating, the illustrations and photographs, along with informative captions, provide most of the book’s substantial heft, as well as its heart. Only by browsing through still life paintings called vanitas, popular in the 16th and 17th centuries, for instance, will you truly grasp what these symbolic masterpieces are meant to convey: the transience of beauty and earthly pursuits.

If I have any quibble with this compendium, it’s that the essays (but thankfully not captions) are printed in sepia tones that make them hard to read without good lighting. But given the subject, this book may be best read while sitting next to a sunny window anyway.